Throughout history, mankind has made continuous attempts to adapt to the physical discomfort of living in hot climates. From taking a nap in the shade to avoid the noon day sun, to creating architecture specifically designed to utilize our planet’s natural ventilation streams, the history of the human race is liberally sprinkled with examples of our desire to keep cool. Yet it is only in the last 100 years have we succeeded in developing mechanical systems that enable us to reach beyond simply taking advantage of our geographical situation to control our surrounding temperatures.

Throughout history, mankind has made continuous attempts to adapt to the physical discomfort of living in hot climates. From taking a nap in the shade to avoid the noon day sun, to creating architecture specifically designed to utilize our planet’s natural ventilation streams, the history of the human race is liberally sprinkled with examples of our desire to keep cool. Yet it is only in the last 100 years have we succeeded in developing mechanical systems that enable us to reach beyond simply taking advantage of our geographical situation to control our surrounding temperatures.

While Willis Haviland Carrier is generally recognized as the ‘father’ of air conditioning, inventors have been fiddling around with the idea of cooling systems as far back as Benjamin Franklin.

It’s Franklin, and Cambridge professor John Hadley, who in 1758 make the discovery that liquids which evaporate faster than water, like alcohol or other volatile liquids, have the pleasing effect of lowering the temperature of an object far enough to freeze water.

Some sixty years later, English inventor Michael Faraday achieves the same result when he compresses and liquidizes ammonia.

The first ice-machine is developed by Dr. John Gorrie in Florida in the 1830’s. He uses compression to produce ice and then creates a system to blow air over the ice to cool the hospital where he works. Recognizing the potential of the device, Gorrie patents his invention in 1851 with ambitious plans to cool buildings all around the world. Unfortunately, his plans fail due to lack of financial backing.

It is the assassination attempt on President James Garfield in 1881 that leads to the creation of the first crude cooling unit. In an effort to keep their wounded President cool and comfortable, Naval Engineers create a box-shaped device filled with wet cloth and blow hot air over the top. This produces a flow of cold air closer to the ground. The device is capable of cooling a room by 20 F but incredibly, consumes half a million pounds of ice within two months.

It is widely recognized that the first ‘modern’ cooling apparatus appeared in the 1830’s and was designed and built by an American physician from Apalachicola in Florida; Dr. John Gorrie. Gorrie’s simple machine consisted of a basic fan which blew across a large block of ice and cooled the wards at the hospital he was working in at the time.

Then in 1881 as US President James Garfield lay on his deathbed, a team of naval engineers designed a method to ease Garfield’s discomfort. They constructed an apparatus that blew air through cloths soaked in water from melted ice. The device succeeded in lowering the room temperature by around 20 degrees but the consumption proved enormous–within eight weeks the process had devoured half a million pounds of ice.

Early 20th century air conditioning or “manufactured air” as it was then called, was seen as a novel industrial solution for steering humidity levels in textile mills with the goal of increasing productivity. But within a short time, further commercial applications were discovered. Food preservation, document protection and the cooling of beer and other beverages became commonplace and more and more cooling stations were built to provide controlled air to neighboring buildings.

It was around this time that Willis Carrier appeared on the scene. Carrier, a mechanical engineer from Buffalo, New York, had a deep understanding of the relationship between dew points, humidity and temperature–an understanding we are told he gained from his experience waiting for a train on a foggy night. In 1902 he introduced a spray-based humidity and temperature control system which heralded the tenuous expansion of air conditioning into hospitals, offices, apartment buildings and hotels.

It was around this time that Willis Carrier appeared on the scene. Carrier, a mechanical engineer from Buffalo, New York, had a deep understanding of the relationship between dew points, humidity and temperature–an understanding we are told he gained from his experience waiting for a train on a foggy night. In 1902 he introduced a spray-based humidity and temperature control system which heralded the tenuous expansion of air conditioning into hospitals, offices, apartment buildings and hotels.

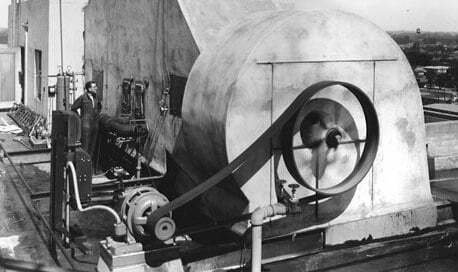

Known as the father of air conditioning, Carrier’s company became synonymous with air conditioning excellence. Carrier devised a method of utilizing chilled coils to cool air and reduce humidity down to an unheard of 55%. Known as his “Apparatus for Treating Air,” the device was able to adjust humidity levels to a fixed setting. This would be the forerunner of what we now know as the modern air conditioner, but it’s good to remember that not only were the early conditioner units extremely large and expensive–use of the toxic coolant ammonia also made them very dangerous!

Willis Carrier first appears on the air conditioning scene in 1902. He invents an apparatus for treating air for a publishing company in Brooklyn, New York. Carrier’s machine blows air across cold coils thus controlling both temperature and humidity of the air inside the building. His device soon attracts the attention of factory owners and industrialists across the country and the Carrier Air Conditioning Company of America is born.

The term ‘air conditioning’ is first coined in North Carolina in 1906. A textile mill engineer by the name of Stuart Cramer invents a ventilation system which produces a mixture of air and water vapor. The resulting increased humidity makes the yarn more pliant, easier to spin and less likely to break.

In 1902, Alfred Wolff, an engineer from Hoboken in New Jersey was assigned the task of fitting out the New York Stock Exchange with a central cooling and heating system. Wolff is remembered for the design improvements he introduced, adapting the existing systems prevalent in the textile mills for use in other buildings. His innovations led to a revolution in the application of cooling technology. Many industries benefited; tobacco and pharmaceutical, as well as the meat and film industries, to name but a few.

In 1911 Willis Carrier presented his ‘Rational Psychometric Formula’ to the American Society of Mechanical Engineers. To this day, the air conditioning industry still uses that same formula.

Air conditioning first received wide public attention at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair where it was presented to almost 20 million baffled yet fascinated visitors. The modern wonder known as manufactured air had arrived.

In 1914, the first domestic air conditioning unit is fitted into the Minneapolis mansion of rubber and leather tycoon Charles Gates. The unit is a monster: 20 feet long and over 7 feet high. But Gates never lives in the house and the monolith is never used.

Soon after their prestigious introduction to the public, the installation of air conditioners began to rapidly infiltrate everyday society. The first private residence to be fitted with the costly luxury was in Minneapolis in 1914 and was owned by Charles Gates, son of John Gates, a notorious but hugely successful gambler of the time.

The first real cool air experience for the average citizen came after 1917 when movie theaters became the next focus of the air conditioning industry. The New Empire Theater in Montgomery, Alabama is the first theater on record to receive a cooling system and in the same year the Central Park Theater in Chicago was specifically designed and built to utilize the new technology. Almost overnight, both venues became hugely popular and attendance numbers soared to unforeseen heights.

In 1922, two crucial breakthroughs in the development of air conditioners were achieved. Again it was Willis Carrier who led the way. First he substituted the toxic ammonia with the far safer dielene (dichloroethylene, or C2H2Cl2). Simultaneously, Carrier greatly reduced the size of the units and at last the cooling systems began to become mainstream with systems being widely installed in office buildings, department stores, private apartments and even in railroad cars.

In 1924, The Carrier Company installed a trio of centrifugal coolers in the J. L. Hudson Department Store in Detroit, Michigan. The pleasing effect on shoppers was duly noted and air conditioning quickly became an integral part of any serious retailer’s marketing strategy. From there it did not take long for serving politicians to get in on the act. Between 1928 and 1930 the White House, the Senate and the House of Representatives were all equipped with cooling systems, as were many other government buildings across the country.

In 1924, The Carrier Company installed a trio of centrifugal coolers in the J. L. Hudson Department Store in Detroit, Michigan. The pleasing effect on shoppers was duly noted and air conditioning quickly became an integral part of any serious retailer’s marketing strategy. From there it did not take long for serving politicians to get in on the act. Between 1928 and 1930 the White House, the Senate and the House of Representatives were all equipped with cooling systems, as were many other government buildings across the country.

The invention of the ‘window-ledge air conditioner’ by J.Q. Sherman and H.H. Schultz in 1931 marks the true beginning of the phenomenal rise of residential cooling systems. The design proved extremely popular, but at prices starting at $10.000 (about $120.000 in today’s money), the units were at first exclusive to the very rich.

Packard is the first auto manufacturer to take the air conditioner on the road. Cooled automobiles appear in 1939 but the control mechanisms are still crude with the only access to the unit still under the hood. Dashboard controls come along a few years later.

Yet some setbacks were also to be had. The spread of commercial air conditioning was greatly hampered during The Great Depression, and when at the World Fair in 1939 Carrier showed off his futuristic igloo, its further development was interrupted by the outbreak of World War II.

By 1942 the spread of air conditioners has gone viral and America builds its first power plant specifically to deal with the demand of summer peak usage.

During the war, many manufacturers converted their production to aid the military effort. Chillers were removed from department stores and re-installed in military plants and returned after the war. Thousands of walk-in air conditioners were manufactured for the US Navy to keep food and other perishables fresh on their ocean journeys. Bespoke portable air coolers were used for airplane maintenance in tropical climates. And yet again we see the name of Willis Carrier leading the way in the further development and functionality of air conditioning systems. Carrier was called upon by the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics to design a system that could reproduce the freezing conditions found at high altitude and thereby carry out crucial testing of airplanes. Many thought the task to be impossible. But once again carrier shone with his ingenuity and was rewarded with the highest honors the US Military could bestow on a commercial company–the Army and Navy E Award

With the end of World War II production returned to mainstream, commercial use and with the US economy about to boom, the future success of air conditioning was guaranteed. Americans in their thousands began to purchase home air conditioning units so that they could enjoy the benefits they had only experienced in larger buildings. Air conditioning became so popular so quickly that soon the demand exceeded the supply and by 1948, yearly production of the home cooling units had reached a staggering 74.000, almost three times that of just two years earlier. It would be another two years before US sales broke the one million barrier for the first time.

In the post war economic boom in the 1950’s, sales of residential air conditioners break the 1 million barrier for the first time.

For a long time, nothing really happens in the world of cooling units. And then in the 1970’s the introduction of home ventilation systems changes almost overnight the face of air conditioning forever. Specially designed units draw air from outside, waft it over cooling coils and blow it through the home.

For a long time, nothing really happens in the world of cooling units. And then in the 1970’s the introduction of home ventilation systems changes almost overnight the face of air conditioning forever. Specially designed units draw air from outside, waft it over cooling coils and blow it through the home.

By now the coolant of choice has become the R 12, aka Freon 12. But in 1994 Freon is recognized as a major factor in the depletion of ozone levels and is banned in many countries. Auto manufacturers are also hit by the new ecological attitudes and are ordered to phase out ozone-depleting coolants by 1996. Forced to comply with world wide public opinion, companies like Carrier and Honeywell then begin the development of more environmentally friendly coolants.

Today, Carrier’s legacy lives on. His spark of genius over a century ago has brought comfort to millions of people all over the world and increased global industrial productivity. Modern air conditioning is cost efficient and easy on the environment.

So when outside it’s sweltering hot and we’re sat inside in our wonderful humid and temperate buildings watching the sidewalk melt, let’s spare a thought for Willis Haviland Carrier’s really ‘cool’ idea.